An Assessment With Gillian Woollett, MA, DPhil, Senior Vice President, Avalere Health

In this two-part conversation with one of the real go-to experts in the biosimilar field and US regulatory process, we talk with Dr. Woollett about the upcoming transition for insulins and other pharmaceuticals in March 2020, when they become regulated as 351(k) biosimilars.

BR&R: Partners Mylan and Biocon recently received a second rejection for its insulin glargine follow-on product, because of the FDA’s inspection results of Biocon’s production facility in India. If they do not get approval by the FDA by March 2020, will they have to submit a new 351(k) biologic licensing agreement (BLA)?

Gillian Woollett, DPhil, MA: In all likelihood yes, but they can’t submit a BLA yet, because there is no reference product for comparison. I’ve been calling this period before March 23, 2020 the “dead zone” and after the “gap year.”

BR&R: Is it possible, since we’re not talking about clinical deficiencies in the product’s data, that some sort of appeal process can be implemented to spare Mylan and Biocon from having to start the BLA process from scratch?

Woollett: We should not presuppose the nature of the deficiencies as any complete response letter is confidential to the sponsor. If the FDA’s concerns are answered by this coming March, there may be no delay. However, after is more of a challenge.

Even if a sponsor is able to submit a BLA on March 24, 2020, it will likely take FDA at least another year to review the application (the “gap year”). Most of the physiochemical and clinical data can be expected to be the same, at least, but this is still a lot of extra work. We likely won’t have an interchangeable insulin until the end of 2021 at the earliest. Hence, as outlined in our paper, this transitional process for insulin will delay competition, not enhance it. And that is a pity for a product as fully characterized as insulin, where we need competition to enhance access.

BR&R: Based on an analysis we did back in June, very few manufacturers have publicly disclosed an interest in producing a biosimilar insulin at the moment. Do you think prospective manufacturers have been discouraged by the transitional timeline?

Woollett: Even in Europe, I think they’ve struggled a bit. Maybe that’s related to the nature of the reimbursement in Europe.

If they are part of the “prequalification” for biologics being undertaken at the World Health Organization (WHO), many other things should be considered in getting global access to your insulin. The WHO’s prequalification effort, albeit limited to date to a pilot for rituximab and trastuzumab, may be particularly helpful to countries with limited drug regulatory capacity. My understanding is that insulins have not been added to the list, as a regulatory matter, but are being considered.

Under this prequalification, if a biosimilar (or other drug) was approved by an agency in a highly regulated market, then that product can go on the list. However, for inclusion on the WHO’s list, the drug also has to be launched—not simply approved. This was addressed specifically in March at the Medicines for Europe meeting in Amsterdam as a problem for biosimilars. The WHO is applying a hurdle over and above FDA approval, which strikes me as a little unnecessary and somewhat counterproductive.

Some companies have extensive experience with their insulin products, but it is not documented in the manner of the highly regulated markets. We hear a lot about real-world evidence in the US, but it is not really being accepted yet.

This is another area I believe the WHO should be going—setting the ceiling as well as the floor, because what we tend to do in the highly regulated markets is overdesign things. We tend to measure parameters, simply because we can (regardless of whether they matter clinically). I call it the “EPA problem”: You only have a contaminant in the environment when you can measure it.

FOUR-LETTER SUFFIXES IN THE TRANSITION

BR&R: Let’s talk about another instance of overdesign in our market, with insulin nomenclature and the transitional process.

Woollett: The FDA has indicated that they will not give these transitional products suffixes to their nonproprietary names. This is super important: The Agency apparently realized just how problematic and expensive changing the nonproprietary names to currently marketed products was going to be, and that they were being tracked adequately today. It would be a challenge to switch every database at midnight, throughout the supply chain, on the date of the transition to include the four-letter suffixes. This is a good decision and huge relief to many stakeholders.

The original draft guidance on nonproprietary names had the suffixes apply to approved biologics and biosimilars. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) had made the case that having a suffix only for biosimilars flagged them as different, and anything that differentiates is necessarily a problem for competitiveness. This is what I call “friction” in the marketplace and will deter switches between reference and biosimilar products. By being fair, the suffix had to apply to all biologics, which raised the problem with the transitional products.

The databanks flagged the problem as a practical matter and massively expensive to reconcile. So, the FDA decided that drugs rolling over to the biosimilars would not receive suffixes. This will apply to all the transitional drugs—hyaluronidases, hormones, insulins, and somatropins, etc. All new products in these categories will get suffixes, irrespective of biosimilar or originator status. So “new” insulins, whether originator or biosimilar, will get suffixes, and this is going to be inordinately confusing, too, but not as expensive to implement.

BR&R: If they don’t apply a suffix to Basaglar®, for instance, and they do so for any transitional product approved after March 2020, it still undercuts the purpose of having the suffix—for identification of individual drugs.

Woollett: Agreed. It is evidence that you don’t need the suffixes in the first place. My overall objection to all of this is inconsistency. If you have a reason to do it, you’ve got to do whatever it is you’re doing for all products… and that is not what is happening.

INSULIN INTERCHANGEABILITY QUESTIONS

BR&R: Well, consistency has not been the FDA’s strong suit. And that goes for the interchangeability of insulins as well.

Woollett: Further, none of the products rolling over can ever be designated interchangeable, because they are not biosimilar in the first place, not even Basaglar.

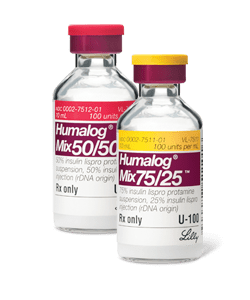

BR&R: Exactly! Here’s the inevitable problem where the rubber meets the road: You’re a patient at a health plan. You have been receiving Lilly’s Humalog® to control your elevated blood glucose levels. Unfortunately, you need to switch health plans next year, and the new plan doesn’t cover Humalog. It covers Novolog® and excludes Humalog or offers it at a nonpreferred copayment tier. The health plan is not interested in whether these two insulin products are interchangeable from a regulatory standpoint. The same is true with the infliximabs and filgrastims.

Woollett: It has always been true that formularies change, but it is still the physician who is doing the prescribing, and so that is OK. For interchangeability, we are only talking about someone other than the original prescriber making the switch.

And by the way, for a biosimilars, it’s not that you are not interchangeable, it’s that you are not yet designated as interchangeable. People are saying that biosimilars are “not interchangeable,” but there’s no such thing. There’s only “designated as interchangeable.” The labels of all the currently approved biosimilars are silent on interchangeability.

BR&R: From a coverage or health plan standpoint, it doesn’t really matter to them.

Woollett: At the plan level, no. Presumably, the plan would just say, “Basaglar® is covered” and simply that there’s no coverage for Lantus®, the reference product for Basaglar®. Today, Basaglar® could be designated as therapeutically equivalent with no extra clinical studies. But after the rollover, Basaglar can never, ever be designated an interchangeable product that the pharmacist can automatically substitute, which seems crazy.

BR&R: Right. Something else that you’ve pointed out in many of your pieces is the problem that these products—outside of being delivered via syringe and needle—they almost always have unique pen-delivery systems. They are a combination of device and product. If you approve these combination products through the 351(k) pathway, will the FDA then have to consider the delivery device in the determination of biosimilarity?

Woollett: That was addressed, if you remember, with the first guidance on interchangeability. The Federal Register notice had two questions outside the draft guidance itself, and one was about human factors and included the devices and self-administration questions. The FDA apparently decided to keep those outside the interchangeability guidance itself, and that was wise. Nonetheless, many of the insulins are essentially combination products.

In part 2 of this interview with Dr. Woollett, we discuss her call for the FDA to move away from totality of evidence, and to “confirmation of sufficient likeness” in its evaluation of biosimilar BLAs.

ts.

ts.